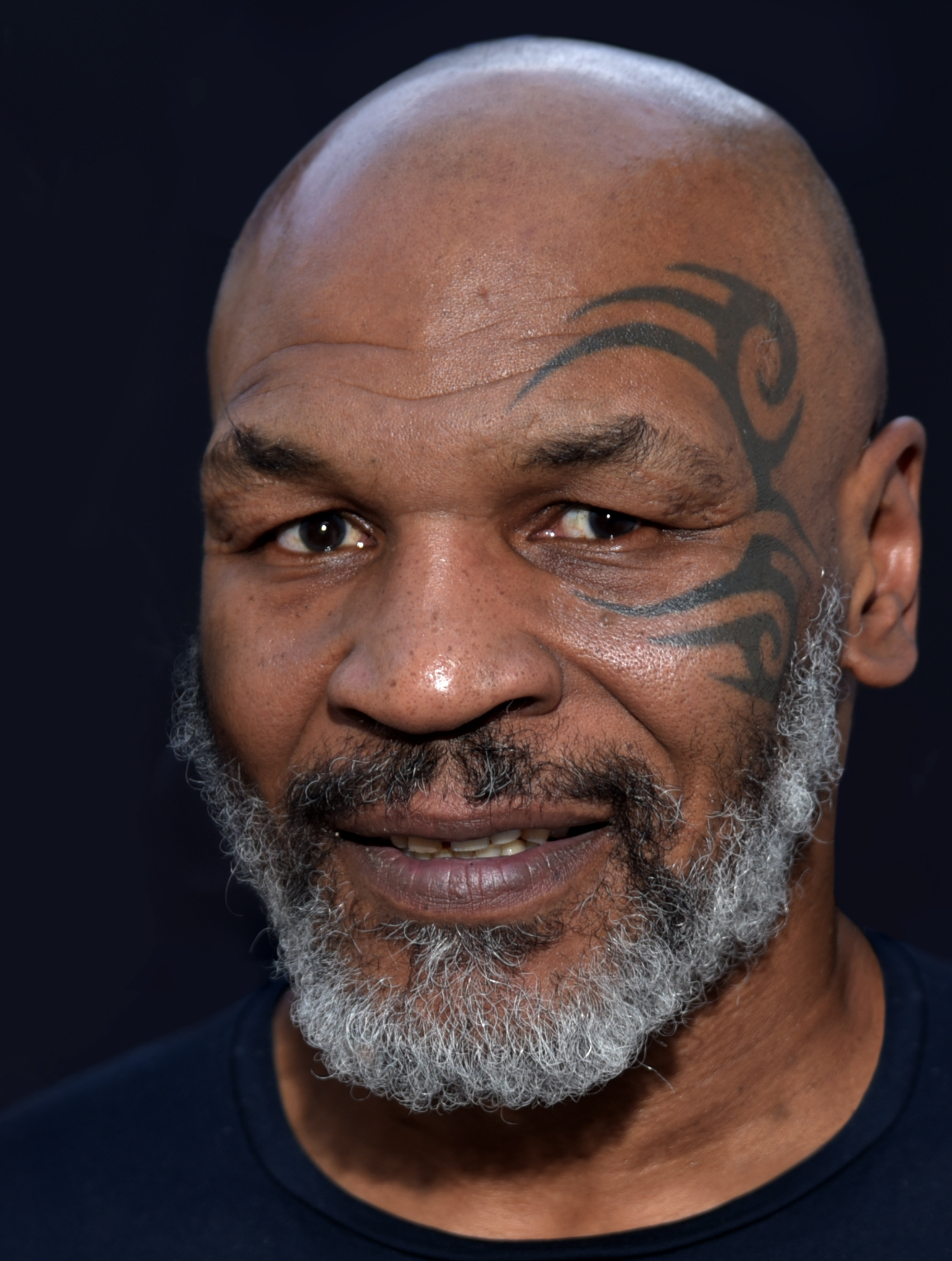

TL;DR: “dynamic, self-adjusting system cannot be governed by a static, unbending policy” is academic for “everybody has a plan until they get punched in the face”.

Mike Tyson said, “Everybody has plans until they get hit.” In the odd process that popular quotations go through, it is often misquoted as “Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the face.”

Tyson also said: “When you see me smash somebody’s skull, you enjoy it.” And: “This country wasn’t built on moral fiber. This country was built on rape, slavery, murder, degradation and affiliation with crime.” Unsurprisingly, neither of those one-liners has made it to as many inspirational slides in keynote presentations and self-help seminars as the one about plans going awry.

Donella Meadows was an environmental scientist, who contributed a lot to the developing field of systems thinking, especially in her books Systems Thinking: A Primer and The Limits to Growth, the latter being an ur-text in the environmental movement. The quote below is of the principles Meadows proposes in her article “Dancing with Systems”, in Whole Earth (published in 2001, the year she died).

I couldn’t find any accounts of Mike Tyson, world champion boxer and quotable killer, meeting Donella Meadows, but they were thinking along similar lines.

“You can imagine why a dynamic, self-adjusting system cannot be governed by a static, unbending policy. It’s easier, more effective, and usually much cheaper to design policies that change depending on the state of the system. Especially where there are great uncertainties, the best policies not only contain feedback loops, but meta-feedback loops–loops that alter, correct, and expand loops. These are policies that design learning into the management process.”

– DH Meadows

There’s a lot going on there. I’m going to need to break it down and make some connections.

“…a dynamc, self-adjusting system…”

There are all kinds of systems. Once you understand them – throw in a working knowledge of network theory and ecology to speed you along – you see the whole world as systems, from the weather, the sun, the wildlife around us, to human cities, supply chains and less visible infrastructure. But I’m most interested in human social systems, and that’s what I’m talking about here. Partly because I lead – and what lead means in this context is a slippery concept – a group of humans in a company, and help leaders in other organisations do work in this area too.

All groups of humans are dynamic, self-adjusting systems. We lived in layers and interlocking lattices of human social networks. Someone does something, others respond then even more people feel the second and third order effects of those actions and make decisions and take actions as they perceive a new reality. Even with just a few people the connections and contexts people are working with and that are affecting each other makes the group a complex-adaptive system. Our brains probably evolved to be so big and capable because of the advantage that being able to live in and get things done with these social networks. There’s a perspective that says that high-order intelligence, language, art, culture and the whole shimmering wonder of humanity is a side-effect of our getting better at living in dynamic, self-adjusting systems.

…cannot be governed by a static, unbending policy.”

Planning is not a bad idea, unless you then pretend that what you have planned is the only way that things can play out. That’s the “unbending policy” that Meadows is talking about. A policy is another word for a plan. This is how we’re going to run things people, please read the paper and then do exactly what it says Or as close as you can…

A static policy is one that once the exhausted planners have agreed upon it, they will not change course. It has emerged in the plan as the answer, and fuck you if you don’t like that answer. This kind of plan, or attitude to plans is utterly pointless.

We’ve always known this. The two best quotes about plans are, of course Tyson (see above) and Moltke, the 19th Century military theorist who said “No plan survives first contact with the enemy.”

The reason that we get “static, unbending” planning is that we are simple creatures who like to understand the world through stories, and once we have a good story we will do almost anything not to let go of it.

So there are plans that might as well be cosmic ordering mumbo-jumbo – universe, please grant me this order of things (and accept the burning of this budgeted amount of money as tribute to your might). There are plans that are fantasy – this is how things will be because I will them to be thus.

You can’t bend complexity to your will by pretending it is just complicated and imposing your will upon it via “levers”.

Complicated vs. Complex

A quick aside on this distinction, because it comes up a lot and I don’t think I’ve written one down before, although I’ve discussed the idea of tame and wicked problems (tame = complicated and wicked = complex). A process is complicated if you can, with sufficient analysis, accurately predict or control the outcome. If a process is complex you may be able to predict the outcome, but only after it has taken place. Connect 4 is complicated, chess is complex. Choosing which trains to get from London to Vienna is complicated, driving around the Arc de Triomphe is complex.

It’s a case of learning to see systems. Have a working model of your own organisation’s systems and then how it interacts with other systems. Start building and refining systems views. Don’t think of them as creating accurate maps, but as a way of exercising your ability to visualise systems. When I started reading about systems thinking I think I was hoping for a simple visual language and methodology for mapping systems. They don’t really exist. It’s useful to borrow from electrical systems, flow charts, and systems diagrams of all kinds, but ultimately you need to develop your own way of seeing them and explaining what you see to others.

No one of these systems views is going to show you the world as it is. They will give you other perspectives. Maybe you combine a few and try to triangulate the truth from their reference data. Whatever you do don’t pick a favourite, it means you are making yourself willfully blind to possibilities.

“…the best policies not only contain feedback loops, but meta-feedback loops–loops…”

That annoying acronym KISS (Keep It Simple Stupid) is useful in mass communications but useless when it comes to managing systems.

None of them are pointless exercises, as long as you don’t cling to them too tightly once the enemy has been sighted, once causes generate effects, once actions start to be taken.

The most useful kind of planning is going will do two things:

- Allows the planners to practice decision-making, responding, thinking about how they will measure and decide upon new courses of actions.

- Sees the things that are within their sphere of control and influence, usually the team or company they are working within, as a dynamic system and how that system might change if they need it to.

“…design learning into the management process.”

This is about cadence of feedback loops. Building in reflection to rhythms of decision-making and review. Simple things that need to be repeated to the point where you don’t think about them, where you know that they are going to happen. But it also means that when you are drawing a system, or being so precocious as to design a system, you need to acknowledge the bits in the flows and the loops where the system can improve itself. It’s not just results, data, metrics that flow back in those feedback loops, it’s learning. “Learning is a deliverable”, is a useful catchphrase we sometimes bandy around. When you’re innovating, experimenting or – more importantly, having the humility to realise that the best laid plans are questions, and the best executions may be ones that bring back answers you weren’t expecting. Think of every outward flow in a systems loops diagram as a question and everything that comes back as a provocation, facts and findings that demand nothing less than another, slightly better question.

Systems thinking, more generally

Over the past few years, I’ve been learning about systems thinking and applying some of what I have learned to both what we do at Brilliant Noise and how the company itself works as a system.

So I know that I know a little, but also that I may be standing at “the peak of Mount Stupid” on this field. Must. Tread. Carefully. Treat this post then, dear reader, as notes from a novice rather than an authoritative account on the topic. (An attempt to dress it up as such would make the sermon from Mount Stupid, I suppose.)

On the recommendation of our excellent team coach, David Webster, I read Peter Senge’s The Fifth Discipline Handbook, a brilliant and applicable collection of practices and ideas about systems thinking in the workplace.

I’m now working my way steadily through Systems Thinkers, a collection of articles and essays by people who have contributed to the field since the 50s, when it was known as cybernetics. It is edited and given a useful commentary by Karen Shipp and Magnus Ramage.

I imagine, if you come back here, you’ll hear more on the subject soon.

You must be logged in to post a comment.